|

| In 1985, we rode this freight from San Antonio de los Cobres to the Chilean border at Socompa. |

That was in 1985, on the route now known as the Tren

a las Nubes (Train to the Clouds); to the best of my memory, it was the last time I rode a

long-distance train – as opposed to commuter and tourist trains - in Argentina

(or Chile,

for that matter). It was enormous fun, as the crew let us sleep in the caboose

and, during the daytime, the engineer even invited us up to the locomotive.

|

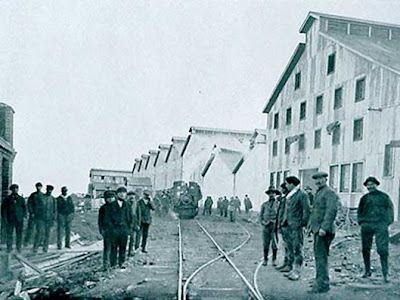

| At one time, numerous train left from Retiro to destinations throughout Argentina. Today, only a handful do. |

Still, I’m often asked about trains in Argentina and,

reluctantly, I tell everybody that, unless you’re a fanatical trainspotter or perhaps even a foamer, it’s best to

stick to the bus or plane. In the 1980s we often took the train, most notably

on our honeymoon from Retiro (pictured above) to Mendoza,

a trip from hell that took place during Argentina’s July winter holidays of

1981. We were on a budget, in “Pullman” seats that reclined only slightly, and

our car filled up with military conscripts who, at that time, traveled for free

as long as they remained standing on a 24-hour marathon. It was not fun.

That no longer happens, partly because there is no more

conscription in Argentina but mostly because there are so few trains, and except

for the one that runs between Constitución

(Buenos

Aires, pictured above in early days) and Mar del

Plata, they’re pretty dismal. According

to the city daily Clarín, a rail network that stretched some 37,000 km in

1950 now covers only 7,500 km, and freight has priority on most of the

remaining track. Trains like El Gran Capitán, which until recently connected

the capital with the northern city of Posadas,

are by all accounts something to avoid (especially in summer, when the weather

is brutally hot and humid). It’s theoretically possible to travel by rail from

Constitución to Bariloche,

but that requires crossing the Río Negro from Carmen

de Patagones to Viedma

and then waiting six days for the connection.

Yet the trains are full, and that’s because they’re cheap.

To quote Clarín, “According to the level of service, the bus can cost nine

times more than the train,” which is the only option for many poorer

Argentines. The train to Córdoba,

for instance, costs 30 pesos (about US$7), while the bus can cost 250 pesos

(roughly US$64). For that reason, the trains sell out early: “In high season,

it’s better to buy 90 days ahead of time – the rest of the year 15 should be

sufficient – and departures are few: the train departs only Monday and Friday.”

That’s why I discourage anybody but the truly determined

from taking long-distance trains in Argentina. My friends Darek

Przebieda and Analía Rupar of Eureka Travel recommend the Tren Patagónico from

Viedma to Bariloche but, even then, they have to admit that the 18-hour trip

averages only about 45 km per hour, and a comfortable sleeper bus would cover the

distance in half the time. For my part, I’ll stick with an excursion on Esquel’s

La

Trochita.